by: Lorenz J. Finison, PhD

Researcher, Archives, Healey Library, University of Massachusetts – Boston

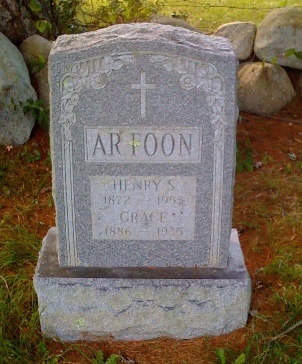

Gravestone of Henry S. and

Grace Ar Foon, Mount Hope

Cemetery, North Scituate,

Massachusetts; taken by

Polly Kimmitt, 15 Sep 2008.

Henry S.和Grace Ar Foon的

墓碑,麻州望合墓園,2008

年9月15日由Polly Kimmitt

拍照

In February 1897, the Boston Herald noted the election of Henry Ar Foon as president of the Winnisimmet (Chelsea) Cycle Club. He was popular with his comrades and “very much Americanized…” His father was Robert Smith Ar Foon, who opened a restaurant and ice cream café on Chelsea’s Broadway with a tea merchant partner, Oong Ar-Showe. His mother was Charlotte (“Lottie”), said to be the first Chinese woman to arrive in Boston. They lived through increasing anti-Chinese agitation, particularly virulent in the west, but occasionally spiking in the east, too, with special restrictions on Chinese women immigrants. Henry Smith Ar Foon, born in 1872, was allegedly the first person of

Chinese descent born in Boston. The family gathered under the umbrella of the Chinese Sunday School of the Mt. Vernon Church on Ashburton Place.

A reporter noted that: “Mrs. Ar Foon . . .looks and dresses like a respectable English woman, and is all satisfaction with her sturdy boy of eleven years and her husband, from whose cropped hair I concluded that they had adopted America as a permanent home.” While the Ar Foon family eagerly assimilated to American culture, they also renewed at least one tie to the homeland, In 1880, Rongjan Tang, who had come to New England as a student member of the Chinese Educational Mission, lived with the Ar Foon family.

“Cropped-haired” Henry had many opportunities to fulfill his parents’ dreams. He joined the Winnisimmets and both officiated and cycled in road races. He entered an East Boston to Revere ten-mile event. Despite a three- and-a-half minute head start he came in thirteenth of fifty-one racers. Ar Foon was better at pool and joined the pool team—cycle

clubs frequently competed at such the winter-time diversions. He also captained the club’s baseball team. In 1896 he was secretary of the “Better Roads League” in Chelsea. Henry was well prepared for Winnisimmet leadership. The Boston Globe headlined that the current president, J.B. Hewes, was under fire and was: “Beaten by a Chinaman.” But the club secretary protested and declared that “Mr. Ar Foon … is not a Chinaman. Mr. Ar Foon is a native of New England, but is of Chinese parentage.”

He continued on through 1899 when the cycling clubs began to die out. Newspaper accounts reported over the next few years that he was the first Chinese juror on an American court; in 1913 a witness for a biracial Chelsea foster-brother, Edward Ar Tick (son of Hee (John) Ar Tick and Margaret Sullivan), who was entangled in a Chinese Exclusion Act proceeding upon trying to reenter the U.S. after seven years in Hong Kong; a prominent member of the Chelsea Yacht Club—other members were witnesses for Ar Tick too; and a clerk, interpreter and private secretary to a prominent Boston millionaire, Dudley L. Pickman. In the 1930s he moved away from Chelsea and settled in Scituate, where he died in 1955. He was buried along with his Worcester-born Caucasian wife, Grace Lloyd (d. 1935) at Mount Hope Cemetery in North Scituate.

Henry Ar Foon and his family showed the desire to be considered real Americans—to belong—during trying times and also of the newspapers’ desire to contrast assimilation to American culture with what they considered the inferiority of foreign ways.

More detail about Henry Ar Foon and references are available in my book: Boston’s Cycling Craze,

1880-1900: A Story of Race, Sport, and Society

(UMass-Press, 2014).

This article originally appeared in the Chinese Historical Society of New England Newsletter, Fall, 2018.